Of course, Europe is only one of the places where timber frame construction goes back centuries. Unsurprisingly, only certain parts of the world with large and readily available forests were able to sustain a well-developed timber

frame tradition. Deserts, the tundra or the high Arctic were areas where trees were rare and not log quality, therefore, timber frame or log construction was simply not possible. Of course, there were many areas of the world besides Europe where vast areas of forest-covered lands offered excellent quality timber for construction. For instance, Jokhang Monastery in Lhasa, Tibet, is believed to be the oldest timber frame construction in the world dating back to the 7th century. Not to mention the classic Japanese timber framing marvel, the pagoda roof. Before we venture off to delve into the historic buildings Asian and American timber framing produced, let us take a closer look at the various styles still standing in Europe.

German Tradition

Where else can you go on a vacation centered on timber frame buildings but Germany? The three thousand kilometers long timber frame road lengthwise crisscrossing the middle of Germany connects the quaint medieval timber frame towns of Bavaria and Baden-Württemberg with the eclectic coastal regions along the North Sea shore. You will see seven distinct varieties of timber frame styles, corresponding with the seven segments of the road, along your journey spanning hundreds of years from the early 1300s to late 19th century. As you begin your trip in the south of the country, you will encounter Lower German timber frame buildings with large spaces on the ground floors that are divided up into three separate sections including storage, a large hall and bedrooms. This style

British Isles

Francophone Regions

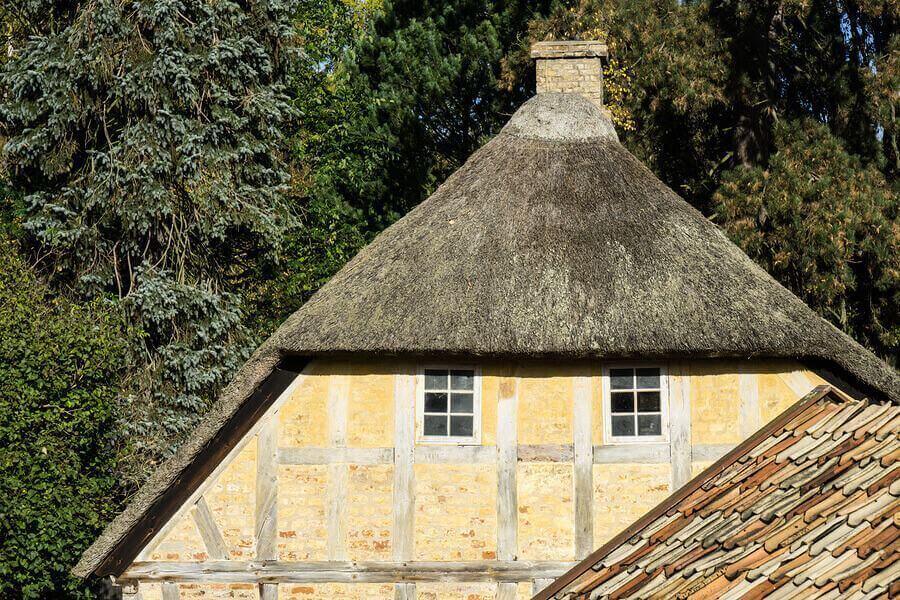

Timber framing and half-timbered constructions are popular in most areas of France and the surrounding regions. In Normandy, timber framing has a long standing history. The capital city of the region, Rouen, features a variety of styles from different historical periods spanning over seven hundred years. From simple frames to elaborate woodworking decorations, the city provides a glimpse back to the Middle Ages. Over the years craftsmen used two major techniques: with the post-in-ground approach, they buried the posts directly into the ground, while with the post-on-sill technique they placed the posts on a beam laid on the ground. Full timber constructions meant increased fire hazard for most medieval cities and the practice of mixing timber framing with stones and composite wall fillers became widespread. In the southern parts of France, half-timbered constructions became a staple of Basque architecture in the 15th century. Although most builders opted for stone

and brick for the construction of the first floors, money often ran out along the way and timber was an acceptable option to adding a second level. Jettied overhangs and second story extensions are commonplace in this region as well as colorful paints of dark red and blue. Baserri is the traditional Basque half-timbered style of building recognizable by its moderately pitched roofs and generous sizes designed to accommodate extended families. Indeed, the Baserri was a central part of Basque culture symbolizing families within settlements both in northern Spain and southern France.

Scandinavian Tradition

The popularity of timber frame building and half-timbered construction methods spread to the northern regions of Europe from the center of the continent in the early Middle Ages. The ability to use various lengths of timber for construction of a frame that builders could fill out with other materials made this technique a particular favorite with inhabitants of northern climates, where sufficient quantity and quality timber was often hard to come by. One of the most widespread and well-known forms of Scandinavian timber framing is the stave construction. In particular, Sweden’s and Norway’s stave churches are renowned examples of the Scandinavian woodworking tradition, although they do exist outside of the region as for instance in Poland and Germany as well. The majority of stave churches date back to the 12th and 13th century and their name comes from the Old Norse word stafr, which is the name of the posts constructed to distribute the weight of the building. These early Christian churches were built with the technique of placing the wooden structure on a stone foundation. The four corner beams created a space that builders filled in with tongue and groove style wooden planks. As the parts fitted into each other through connecting grooves, the entire building locked the beams in place for a sturdy construction. Naturally, stave churches are only one kind of timber frame styles within the Scandinavian tradition. Another type of plank house called bole or Skiftesverk was mainly used for barns, homes, and farm buildings, whereas half-timbered construction dominated architectural styles well into the 1800s. Finally, the early windmills in the Netherlands are prime examples of timber frame buildings and they also actively helped in establishing the widespread practice of using timber logs for construction with their ability to efficiently saw through large logs.

Asia

Post and lintel construction using various materials, including timber, has been one of the oldest methods of creating a framed opening. Many of these constructions have been exceptionally well preserved in different parts of Asia, providing a glimpse into the ingenuity of timber framing. Even today, the classic Chinese gates we learned to associate with Chinatowns of major cities in the west are magnificent, yet simple forms of post and beam engineering: two beams planted in the ground holding up a horizontal sill connecting the posts to frame a portal. In fact, the main difference between traditional Asian construction and western construction methods is in the conceptualization of the wall. While western architecture used walls as load bearing parts of a building, the Asian tradition perceived walls as spatial demarcations that simply filled in the area between structural beams. You can easily see this concept at work when considering the classic Japanese shoji sliding doors and rice paper walls. Asian joinery also developed a high degree of specialization as diagonal braces were very rarely used as support structures. Naturally, different regions across the continent developed their own architectural style and methods of construction.

The previously mentioned Jokhang monastery complex in Tibet is only one part of the versatile Asian tradition. In fact, Jokhang itself bears evidence of Indian, Chinese, and Nepalese design influences. Many other rural monasteries, such as the Ragya monastery from the early 1700s, followed similar construction techniques that incorporated mortise and tenon joinery with elaborate bracing and intricate post carvings throughout the building complex.

Chinese craftsmen even developed a specific interlocking wooden bracket system that made it possible to securely join rafters to building posts without fasteners. These dougong brackets became particularly popular in the 6th and 5th centuries BC. Over the centuries, Chinese builders developed the dougong into one of the main support systems that allowed them to create reliable constructions that were able to cope with forces challenging structural integrity, such as earthquakes. Over time, brackets acquired decorative elements that were emphasized with the use of bright paints and stylized artistry.

North America

Half-timbered construction became particularly preferred in areas settled by German immigrants who brought their craftsmanship and knowledge of wooden engineering with them from the old country. Even today, timber frame barns and halls are one of the best-known trademarks of Amish carpentry. In the North American colonies, the most popular choice for timber beams was oak with the occasional addition of white pine or poplar. Interestingly, many early colonial builders simply did not have the time to season their timber and opted for installing their beams green. This was the case with the oldest

Often, it is difficult to recognize historical timber frame construction as their façades have changed many times over the centuries. Subsequent owners covered up the timber with clapboards or siding to make their home fit better with the dominant architectural styles of their times. Nevertheless, some structures remained the same. Barns, for instance, benefited greatly from the spacious interiors timber framing was able to provide and for this reason, timber frame barns, which started out as the Dutch barn tradition in North America, have remained in use well after the industrial production of nails and screws that made the popularity of timber frame structures decline.